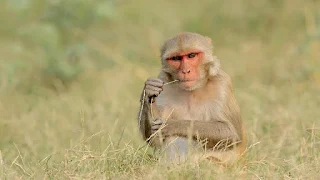

Chinese biologists succeeded in cloning a rhesus monkey using the method of transferring the nucleus of a somatic cell into the cytoplasm of an egg, which British scientists used to clone "Dolly the sheep" in 1996.

The journal Nature Communications notes that, according to the scientists, “the somatic cell nuclear transfer method had already been used successfully to clone a long-tailed macaque. But rhesus monkeys were not cloned in the same way. So we devised an approach that greatly increased the probability of successful cloning, allowing us to produce a healthy male.” A clone of this animal.

It is noteworthy that in 2018, a team of biologists headed by Professor Sun Qiang, Director of the Primate Study Center in Beijing, managed to clone two long-tailed macaques. But they were not successful despite numerous attempts to clone the rhesus macaque in the same way.

But now thanks to improvements in the cloning method, by replacing some of the cells in the cloned embryos with their counterparts from embryos obtained using artificial insemination, they have successfully cloned a rhesus macaque.

It turned out that this step, as it turned out later, greatly increased the probability of the embryos surviving, and thanks to it, scientists were able to obtain 11 supposedly viable embryos, 7 of which were implanted in the wombs of the surrogate mothers. But only two of the cloned embryos took root, and only one of them was born.

According to the researchers, this male rhesus macaque has been living for more than two years, is in good health, and has no obvious or hidden congenital defects in the functioning of his body. This gives hope that subsequent improvements in cloning techniques will allow scientists to begin cloning large numbers of primates for medical and biological research that currently use ordinary monkeys.

Scientists determine the age of the "kelp forest" at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean

The most productive underwater ecosystems on Earth arose more than 32 million years ago.

Scientists from the United States and Europe found that so-called kelp forests, the most productive underwater ecosystems on Earth, arose at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean at least 32 million years ago, and not 14-15 million years ago, as was thought in the past. The press service of the University of California at Berkeley said that this calls into question prevailing ideas about the evolution of its organisms.

“It was first thought that kelp forests could not have appeared in the Pacific Ocean 14 million years ago, because the organisms associated with these ecosystems did not exist before that,” the university’s press service quoted Cindy Lowe, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, as saying. "Proving the existence of these biomes that were originally inhabited by organisms completely different from invertebrate and vertebrate animals."

It is noteworthy that the so-called kelp forests are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth. These are shallow areas at the bottom of the Earth's oceans where dense clumps of brown kelp algae and other plants grow. Its rapidly growing biomass forms the basis for a large number of invertebrates and vertebrate organisms, including molluscs, sea urchins, crustaceans, fish, seals and sea otters.

The researchers found that these important marine ecosystems appeared in the Pacific Ocean at the beginning of the Oligocene era, more than 32 million years ago. Scientists reached this conclusion during excavations in the western regions of Washington State in North America, where there are rocks that formed at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean in the distant past.

In these rocks, scientists discovered many remains of algae roots and imprints of their stems, in addition to other evidence that the western shores of the modern United States at the beginning of the Oligocene era were covered with kelp forests. This, as scientists have noted, pushes the time of its appearance into the past by approximately 18 million years, as the age of the oldest fossil evidence of its existence was 14 million years earlier.

Scientists hypothesize that ancient kelp forests served as a major habitat for the enigmatic desmostilians, large marine mammals similar in size and appearance to hippopotamuses that lived off the coast of the Pacific Ocean from the beginning of the Oligocene until the end of the Miocene. Until now, paleontologists have not been able to identify the ecosystems in which These creatures lived there. The researchers concluded that their extinction about 7 million years ago made way for modern kelp forest animals.