A 53-year-old man from Chile developed sore throat, hoarseness and cough before he was diagnosed with avian influenza.

The patient's symptoms worsened during March 2023, and he was admitted to the hospital, in the intensive care unit.

After being treated with antiviral and antibiotic medication, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that he was still being monitored in the hospital.

Upon testing, lab results conducted by Chilean and US health officials revealed two viral infection-related mutations in the PB2 gene, which are believed to make the virus more lethal and transmissible to humans.

The British newspaper "The Sun" reported that this comes just weeks after the execution of 40,000 chickens in central Chile.

The new laboratory analysis looked at the virus found in the lungs of a patient who lived in the Antofagasta region of Chile. According to the WHO case summary, it is believed that he became infected through contact with sick or dead birds.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stressed that, despite the new mutations, the current threat to people remains low.

At the moment, there is no evidence that the mutated virus has spread to other people or that it has the ability to evade medicines and vaccines.

The CDC said there was no evidence yet that the mutations would make it easier for it to take root in a person's upper lungs, a development that would raise concerns about spreading to humans.

The newspaper "The Sun" that scientific experts are now urging the government to create a new vaccine for bird flu.

Bird flu

The NHS explains that avian influenza is "a contagious type of influenza that spreads among birds".

In "rare cases" avian influenza can infect humans, with some strains of concern reported:

- H5N1 (since 1997)

- H7N9 (since 2013)

- H5N6 (since 2014)

- H5N8 (since 2016)

The NHS says: "H5N1, H7N9 and H5N6 do not infect humans easily and are not usually transmitted from person to person. However, many people around the world have been infected with it, resulting in a number of deaths."

Current avian influenza infections have been identified as type A H5N1.

It is noteworthy that about 868 human cases of infection with the H5N1 virus were reported during the past two decades and more than half of the cases (456) were fatal, according to the World Health Organization.

There have been some reports of human-to-human transmission, but this is very rare. And the vast majority of those infected were exposed to the infection directly from the birds.

Concerns have been raised in recent months because of the "unprecedented" outbreak of avian influenza among birds and mammals.

Experts worry that the sheer scale of the current outbreak may give the virus more opportunities to mutate, which could enable H5N1 to spread better in humans.

How can bird flu spread?

Avian influenza can spread through close contact with an infected bird, whether it is alive or dead.

This includes touching infected birds, handling droppings, or killing or preparing infected poultry for cooking.

If someone has avian influenza, the main symptoms may include:

- High fever, feeling hot or shivering

- Muscle pain

- Headache

- Cough or shortness of breath

- Diarrhea

- Get sick

- Stomach pain

- Chest pain

- Bleeding from the nose and gums

- Conjunctivitis.

Symptoms usually appear up to five days after the original infection. Treatment includes antiviral medications that may help reduce the severity of symptoms.

Ancient viruses hiding in DNA may hold the key to treating lung cancer

Researchers say remnants of ancient viruses transmitted thousands or even millions of years in human DNA may pave the way for better cancer treatments in the future.

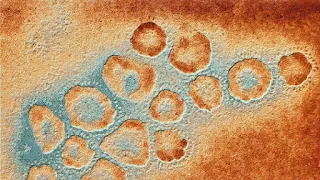

Scientists at the Francis Crick Institute have been studying lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, to understand why some patients respond better than others to immunotherapy.

In the study, published in the journal Nature, they found that the remnants of old cells can be activated by cancer cells. They discovered that this could inadvertently help the immune system target and attack the tumor.

The scientists report that these "remarkable" findings can be used to help more people survive lung cancer by promoting cancer treatment or even prevention.

"This work opens up a number of new opportunities to improve patients' responses to immunotherapy, a critical step in helping more people survive lung cancer," said Julian Downward, associate director of research and head of the Oncogene Biology Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute.

By monitoring the activity of immune cells in mice with lung cancer and in human lung cancer tumor samples, the researchers found that antibody-producing white blood cells called B cells contribute to the lung cancer immune response by producing tumor-binding antibodies.

When they looked at the target of this response, they found that the antibodies recognized proteins expressed by ancient viral DNA, known as endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), which make up about 5% of the human genome and are passed down from historical infections of our ancestors.

In most healthy tissues these viral genes are silenced, but in cancers they can be awakened.

"We now know that regions of B cell expansion can help us predict a positive response to checkpoint inhibition," Downward explained. "With further research, we can work to boost B cell activity in a targeted manner to patients least likely to respond."

"Retrovirals have been hiding as viral footprints in the human genome for thousands or millions of years, so it's great to think that the diseases of our ancestors might be the key to treating the diseases of today," said George Kassiotis, head of the Viral Immunology Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute. We can look forward to developing a cancer treatment vaccine consisting of activated autoretroviral (ERV) genes to enhance antibody production at the site of a patient's cancer and hopefully improve the outcome of immunotherapy."

Dr Clare Bromley, from the charity, said more research was needed to develop a vaccine for cancer, but added: "However, this study adds to the growing body of research that could one day see this innovative approach to treating cancer a reality."

Great

ReplyDeleteGood

ReplyDeleteGreat

ReplyDeleteSuper

ReplyDelete